PUNCHING WAY ABOVE HIS WEIGHT

In this essay I argue that this idiosyncratic painter is one of the ten most original British artists working in the first half of the 20th century.

Sam Rabin is back in Town. Forty years after his triumph at the Dulwich Picture Gallery one-man show in 1985, my hero is again strutting his stuff, in London at the Ben Uri Gallery. Sam was more than a bit of an entertainer – a showman for large part of his extraordinarily diverse career. The other side was a highly reserved, deeply serious and dedicated personality.

He was born into a first-generation immigrant Jewish family in the Cheetham Hill district of Manchester. You could not arrive at a more welcoming first base for refugees escaping from the Russian Pale of Settlement where Jews were confined by law between 1815 and 1817. Cheetham Hill at the time already had seven synagogues. The community found work in the emerging Manchester garment industry. The city of Manchester had a warm tolerant and respectable indigenous population willing to make room in tightly terraced streets for the newcomers. Not exactly the promised land but good enough for the Rabinovitch family. Sam flourished at school and won a scholarship to the Manchester School of Art at the ridiculously young age of 11, the youngest person ever to do so. Shortly after he announced that when he grew up he was going to be the strongest man in the world and in case that was an insufficient ambition, also a great artist. It wasn’t long before he was secretly testing his physical capability with the school’s boilerman, an ex-miner, who taught him catch-as-catch-can wrestling. At the same time he developed a voracious appetite for learning drawing, and composition, from his tutor Adolphe Valette. The dapper man from St. Étienne was himself a diligent practitioner of the ‘French Method’ of teaching fine art, i.e. by demonstration.

It is all in the book. My point of repeating it all is that when arriving in London in 1921 to attend the Slade School of Art, Rabin was very physically fit and a very handsome young man and was on his way to fulfilling his stated ambitions. He was a product of Manchester but he was soon to become a Londoner.

He threw himself into a whirlwind of activity. By the day he was Tonks’ favourite pupil at the Slade in Gower Street. In the evenings he would attend boxing and wrestling lessons at the Ashdown Club in Pentonville where his coach, George Mackenzie, recommended him as an Olympic wrestling prospect. He also found time to attend the big fights at Olympia, Royal Albert Hall, and the National Sporting Club in Covent Garden, where British boxers Ted ‘Kid’ Lewis, Joe Beckett, Len Harvey and one brilliant Frenchman, Georges Carpentier were regularly competing. Following a brief period when he shared a flat with John Mansbridge in Camden Town, he found lodgings at Constantine Road, Hampstead and rented a studio in Ebury Street. Whilst at the Slade, Rabin took an interest in sculpture, being particularly skilled at carving into stone. This resulted in him taking private lessons from Jacob Epstein at the American’s studio in Guildford Street, Bloomsbury. Later, working as one of a team of sculptors carving the figures on the new London Transport HQ at St. James Park, he would be in almost daily contact with the young Henry Moore and Eric Gill.

It would be fair to say that as he crisscrossed his adopted metropolis daily he met up with a great many in the British creative milieu. We know he was familiar with the habits of the elder statesmen, Augustus John and William Orpen, who he scorned as the ‘Café Royal lot’, and the influx of talented fellow Jews from Eastern Europe, who had startled their tutors at the Slade School and the Royal College of Art. Their arrival was seismic. Out of the ten newcomers, shared between these two institutions, at least five turned out to be amongst Britain’s finest artists of the 20th century; Bomberg, Gertler, Bernard Meninsky, Barnett Freedman and in his eyes Sam Rabinovitch as he did not shorten his name to ‘Rabin’ until he became a professional “All-In” wrestler in the early 1930s. During their studies and early careers they would often rub shoulders with the likes of the Nash brothers, C.R.W. Nevinson, Stanley Spencer, William Roberts and Dora Carrington, all products of the English middle class. As John Russell Taylor, the Times art critic, observed: ‘To achieve the right sort of artistic standing one had to begin with the right sort of social standing, which was certainly not working class and very unlikely to be Jewish.’ Although part of the milieu Sam remained on the periphery and kept himself to himself. He did not join any clubs or cliques, but did strike up a close friendship with Barnett Freedman, ‘Soc’, short for Socrates, much because of their shared enjoyment of passionate debate.

While Rabin was taking a valuable twelve-month sojourn in Paris, in 1925, where he was absorbing all the new Post-Impressionist trends (often dismissed by Sam as being by ‘squares & circles merchants’), and the teaching of internationally famous sculptor, Charles Despiau, Freedman was having to lend money and essentially fund the experience for his perennially broke friend. Sam’s letters are here to see. Their close relationship lasted until Freedman died from a sudden heart attack in 1957; he was only 57. They were total opposites in every respect. Where Rabin was tall, good looking and athletic, Barnett was small, pear shaped, prematurely balding and shortsighted. Rabin tended towards the silent, slightly moody type, deeply suspicious of commerce in all its manifestations, and impressively grave and driven. His affection for his friend is best found in the delightful caricature he does of the little man and the astonishing quality of his bronze portrait bust (lost for decades but now thankfully rediscovered).

And so the story goes on. Rabin gets his Olympic bronze medal at the 1928 Olympic Games in Amsterdam, and then, unaccountably, given his disdain for the commercial, switches from amateur to professional wrestling. Subsequently he has a spell as a stunt man for Alexander Korda in historical Ealing Studios box office hit films. Then he pops up at the BBC as a singer of lieder, German art songs, and opera before being recruited into an army group of classical musicians to entertain the troops at home, and in Europe from 1939. On demobilisation he returns to the BBC. In 1949, he is offered employment as a teacher of drawing at Goldsmiths’ College, in New Cross, South London. It is his dream job. He enthusiastically embraces the opportunity (grabs it with both hands) and his commitment is rewarded by his students’ respect and progress. His students included Bridget Riley and Mary Quant. Due to differences over new teaching methods he leaves Goldsmiths’ in 1965, and takes up an appointment at Bournemouth College of Art where he taught for 20 years until 1985. His final teaching post was at Poole Art Centre where he inspired his students until shortly before his death in 1991.

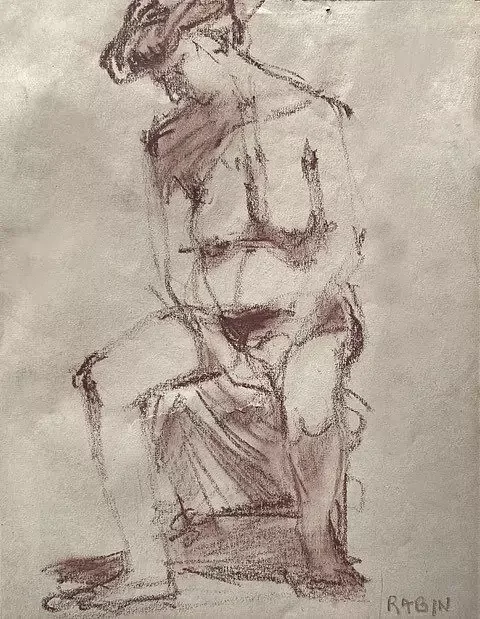

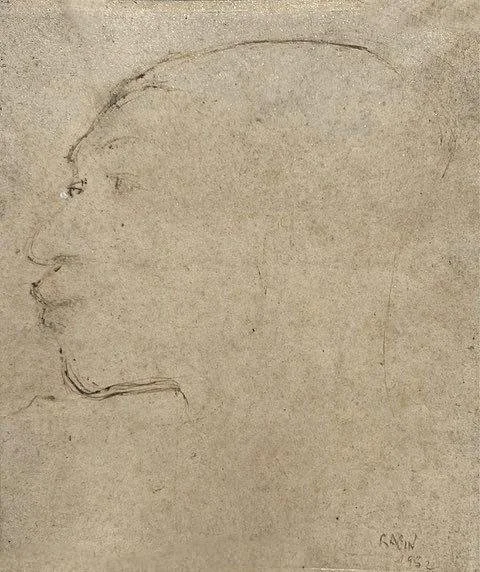

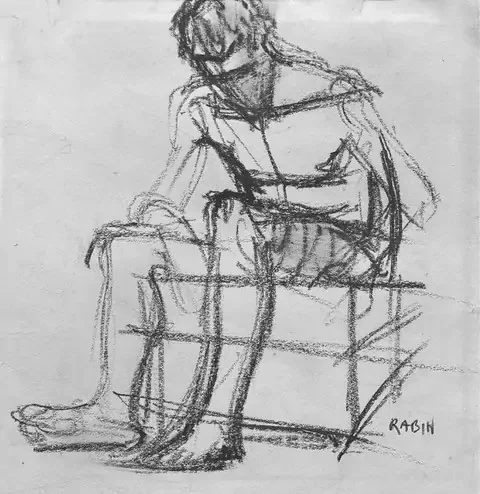

I might suggest that it is this departure from London that fires up Rabin’s latent creative energies and capacity to teach. He embarked on his most productive phase. The viewer of his work need not be a fan of boxing. Rabin’s pictures are in no sense fashionable, but they are stylish in a way that all good art was a fluidity that engages the eye. It emerges from his total commitment to the precise geometry of his subject matter. The ring is his frame for endless exploitation. The tighter the area, the more the artist is forced to plumb his or her creative resource. Rabin remained totally disciplined. We soon recognise he has a rare ability to know when to stop, a restrained sparseness, he shared with some of the greatest names in art, Mondrian, Morandi, Rothko, and Chardin, for example. Not bad for a boy from Cheetham Hill. Bill Crow 29/12/25